Talking to Kids About Suicide

Suicide prevention may be an uncomfortable topic to discuss with children and adolescents. But much like sex and intimacy, domestic violence and substance misuse, the topic can have serious consequences if left unaddressed.

“We don’t shy away from talking about regular physical health check ups. I think talking about suicide is a part of recognizing that mental health matters,” said Julie Goldstein Grumet, the director of the Zero Suicide Institute and senior healthcare adviser for the Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States, and many people struggle with suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts. Discussing suicide with children and adolescents can help them better respond to those thoughts and ask for help, whether for themselves or for friends. Both younger and older children may need different approaches to help them understand suicide.

This article is for informational purposes. If you or somebody you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts or a mental health crisis, please reach out to a mental health professional or call the the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

Understanding Suicide

The 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identifies suicide as the second leading cause of death among high school-aged youths. The survey also notes that:

18.8%

of students reported having seriously considered suicide.

15.7%

of students made a plan on how they would attempt suicide.

46.8%

of LGBTQ students seriously considered attempting suicide.

Experts say that these alarming statistics should underscore the importance of adults learning how to talk about suicide.

“It’s important to educate yourself about the magnitude of the problem. If you don’t know or are not aware that there’s a problem, you don’t know how to look out for it,” said Brett Marciel, chief communications officer for the Jason Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the awareness and prevention of youth and young adult suicide.

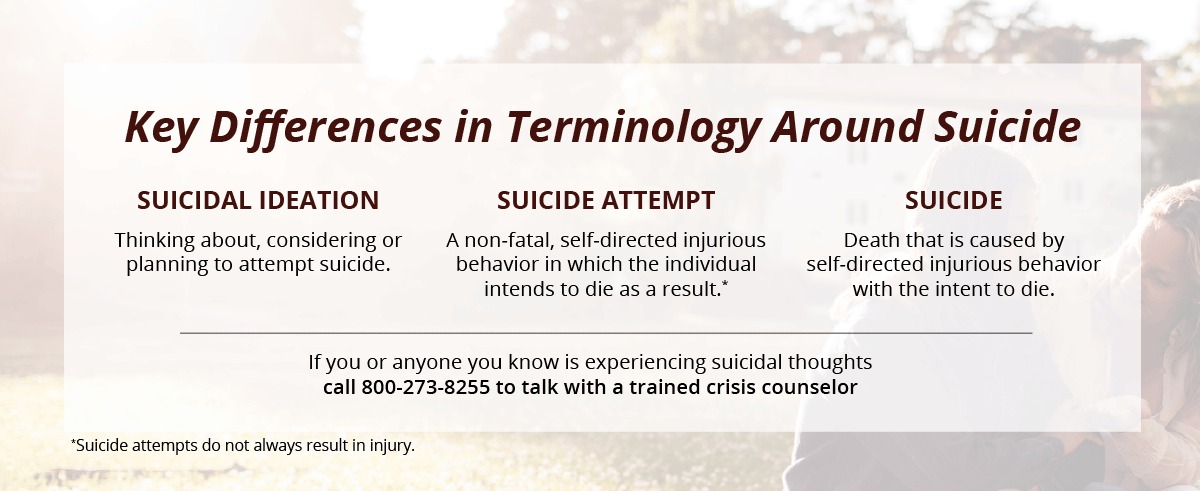

Key Differences in Terminology Around Suicide

There are key differences in terminology around suicide that are critical to distinguish from one another. It’s important to know them in order to understand the larger context around suicide.

Suicide: Death that is caused by self-directed injurious behavior with the intent to die.

Suicide attempt: A non-fatal, self-directed injurious behavior in which the individual intends to die as a result. Suicide attempts do not always result in injury.

Suicidal ideation: Thinking about, considering or planning to attempt suicide.

Being able to identify warning signs and risk factors related to suicide is an important component of discussion. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ fact sheet on suicide (PDF, 94 KB), warning signs can include:

- Threats or comments about killing themselves, i.e., “I wish I wasn’t here.”

- Giving away their possessions and getting their affairs in order.

- Social withdrawal or saying goodbye to friends and family.

- Increased alcohol or drug use.

- Aggressive behavior and dramatic mood swings.

- Preoccupation with talking, writing or thinking about death.

- Impulsive or reckless behavior.

How To Talk About Suicide With Youth

Talking about suicide can be very intimidating, or triggering, to children and adolescents. To learn more about suicide by age group, click the buttons for more information.

If you or anyone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts call 800-273-8255 to talk with a trained crisis counselor.

Adults need to create a safe, nonjudgmental space that allows for complete honesty. The focus of the moment should be on listening, understanding and empathizing. Children and adolescents need to feel that adults can find them the help they need to manage intense feelings so that they do not have to keep feeling hopeless or withdrawn.

“If someone is thinking about suicide because of issues at home or a breakup, whatever the reason that they’re having these thoughts to begin with, the conversation that you’re having is not to try to solve the issue that got them here,” Goldstein Grumet said.

While younger kids may need more general guidance on suicide prevention, older kids may need a more direct approach to understanding suicide. SocialWorkLicenseMap.com asked experts to share their strategies for approaching these conversations with youth at different age levels.

Conversation Recommendations for Elementary School Children

(ages 5–10)

The goal of this age group is to understand the different emotions we experience and feel comfortable sharing them.

Help children identify their feelings. Children need to start to learn how to identify and express their emotions freely and build social and conflict resolution skills. Adults can step in to help them measure the weight of their feelings. For example, you could ask, “If you feel really mad, can you tell me about it? How mad? How does that feel in your body?” According to Goldstein Grumet, “Conversations like this are critical for them to have the foundation to do well later in life to navigate big feelings and recognize that they’re not overwhelming to people around them.”

Establish adults as a trusted place to turn. Remember that the idea of forever is less concrete for younger children. This age group may need a broader approach to discussing suicide prevention, Goldstein Grumet said. You can do this by using less direct language to help set up the foundation for understanding suicide. Ask questions such as, “Do you ever wish you could go to sleep and never wake up?” or “Would you ever do something to hurt your body?”

Gently address the broader concept. The goal of discussing suicide with children of this age group is not to be introspective and self-identify if they may be struggling. The focus should be more about looking out for others and being there for a friend.

Conversation Recommendations for Middle School Adolescents

(ages 10–13)

The goal of this age group is to focus on understanding when to seek help.

Distinguish between a good and bad secret. Due to their maturity level, it can be difficult to tease out what information is worth keeping. For example, if a friend confides that they are thinking of suicide, middle school-aged kids tend to have a sense of fearfulness that they are betraying that friend by telling someone this secret. They may have difficulty distinguishing what is a secret worth keeping.

Underscore that telling somebody can protect their friends. Something that could get their suicidal friend significantly hurt should not be kept secret from adults. Kids can be supportive by saying, “I’m going to get you help because I love you and I care about you.” Alternatively, they do not have to disclose to that friend that they intend to tell an adult. Making the safest choice is imperative.

Validate difficult but good choices. It is important to tell children in this age group that what they did was right. You can tell them: “I’m so proud of you. That must have been really hard, but you did the right thing.” Death is far harder to get over than a friend being upset with a child for a day, a month or a year. They can repair their friendship if that friend is still alive.

Conversation Recommendations for High School Teens

(ages 14–18)

The goal of this age group is to help them utilize their support systems when they’re feeling bad.

Be more open and direct. High schoolers are likely to have already been exposed to the ideas of mental health and suicide, whether from their peers, school or the media. You can ask them questions like, “Have you had thoughts of suicide?” or “Are things so bad right now you wish you were dead?”

Don’t cast judgment. It’s hard to pinpoint a singular cause of suicidal thoughts; it is often multidimensional and includes underlying factors. Relationship breaks, moves or transfers to a new school can be risk factors, but it’s not an adult’s place to cast that kind of judgment on a young person who doesn’t have the same life experiences as adults. It’s about validating their experiences and feelings with an empathetic outlook.

Empathize. Understand that you’re unable to fix that breakup or solve the fight with the friend, but you can listen closely and empathize with them. Say things like: “That sounds like it was really hard for you. That sounds like something that you really haven’t experienced before, and it’s giving you overwhelming feelings.”

Remember that talking about suicide doesn’t mean you are putting the idea in their head. This is a common myth. Bringing up suicide to a teen raises the idea that you are an adult who is open to having these kinds of emotionally charged conversations.

“What we don’t want is to give kids the idea that even talking about suicide is shut down because if you do that (should they be at risk), you’ve already given them the signal ‘don’t come to me,’” Goldstein Grumet said.

How To Help Children and Adolescents in Trouble

Various adults in children and adolescents’ lives can play important but different roles in addressing suicide. For parents, it can be easy to think of suicide as a terrible tragedy that happens to someone else’s family.

“There’s no one exempt from suicidal thoughts,” Marciel cautioned.

If a child does verbalize suicidal thoughts, it’s important to take them seriously. These threats can be veiled, like “You’d be better off without me,” or straightforward: “I’m going to kill myself.”

“Suicide prevention and student health take a comprehensive approach that has to be hit by multiple topics. The more prepared we are and everyone knows their role and how to respond, the better the outcomes are for everyone involved,”

— Julie Goldstein Grumet

Educators may also hear and see signs that a child or teen is considering suicide. If that disclosure happens, it’s important for educators to remember that they are not crisis counselors and should direct students to mental health professionals. Mental health care takes a support system, and the educator’s role is to understand the problem and its context within the school and community while assisting the student in finding help.

“Suicide prevention and student health take a comprehensive approach that has to be hit by multiple topics. The more prepared we are and everyone knows their role and how to respond, the better the outcomes are for everyone involved,” Goldstein Grumet said.

Parents can also monitor children’s media consumption. Suicide and other forms of violence tend to be prevalent in TV and gaming. If a child is overwhelmed by media depictions of suicide, consider opening a conversation with: “What would you do if you were as sad as Rob in that episode? Who would you tell?” Use natural opportunities to make these conversations a part of interactions with kids so that when an emergency or crisis does emerge, the child doesn’t feel like they’ve never talked about this before.

If you are monitoring what your kids are watching, explain why: “When you watch a lot of these things, you can be exposed to information that can be overwhelming that you might not understand, and I want to navigate it with you and answer your questions.”

You can liken it to wearing a seat belt when you’re driving in the car. These are preventive steps to educate kids about suicide, instead of waiting until they come to you with suicidal thoughts or it becomes critical.

Resources for Suicide Prevention

Here is a comprehensive list of organizations that are dedicated to learning about suicide prevention, understanding suicide, talking about suicide and getting help.

- The Crisis Text Line: A crisis hotline for youth. Text “Jason” to 741741 to communicate with a trained crisis counselor.

- Suicide Awareness Voices of Education (SAVE): An educational organization that helps survivors of suicide and educates others on suicide prevention.

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention: An organization for suicide prevention, resources for suicide prevention and how to discuss suicide prevention.

- National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention: A public-private national partnership for suicide prevention that tackles community, health and ending stigma.

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center: A site offering suicide prevention resources, programs and trainings as well as education on suicide.

- #BeThe1To: Standing for “Be the one to help save a life,” this organization aims to help spread awareness on how to communicate with someone who is suicidal. It also includes a list of multimedia resources and real life stories.

- The Trevor Project: An organization dedicated to suicide prevention and crisis intervention among LGBTQ youth.

- The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: A number to call in case of emergency for confidential support from a trained crisis counselor (1-800-273-8255).

- National Council for Suicide Prevention: A coalition of nonprofits for suicide prevention.